One of the things I’m particularly interested in exploring, and have been pondering for the last year or so, is the actual act of taking a photo, as distinct from the photographic end product. There’s something about that process of looking, composing and capturing that seems to tap into something fundamental, though I don’t at this stage know what it is. I’m hoping that through developing these walks over the next few months, which are all about people experience that act in different ways, I can come to some better understanding of it.

This post is therefore a bit of a sketch of some ideas of mine framed by a few things I’ve read (saved on my Tumblr).

To give me a sense of where the wider conversation about photography is at, I’ve been subscribed to the RSS feed for Medium’s Click The Shutter collection of short posts about photography for the last few months. Most of it is lightweight but the occasional gem pops through and here are a couple that caught my eye for complimentary but very different reasons.

This Is You On Smiles refers in its title to the classic anti-drugs commercial This is your brain on drugs, so you know immediately where author Dave Pell is coming from. That our modern obsession with photographing and videoing every important event in our lives is somehow destroying the memory of them. Usually I reject this line of thinking but there is a valid point in there. When you bring a recording device into an experience you change it in some quite fundamental ways beyond the obvious awareness of the lens or microphone. The act of mediating your experience through a machine is not to be underestimated.

Where I disagree is that this is necessarily a bad thing. Our experiences are constantly mediated and manipulated by external and internal processes. Noise pollution can make an otherwise beautiful sunset an upsetting moment, or a bad mood from an argument can adversely effect other unconnected experiences. And yes, feeling the need to photograph something for posterity can diminish the experience of the thing itself. But it can also add to it.

I confess I wish I’d written Alex Furman’s The Practice Of Photography, also on Medium, because it perfectly captures why I do Photo School, but let’s unpack the conclusion for the purposes of this subject.

There’s one thing that practicing photography does to you that is immensely valuable and often overlooked. It forces you to see the world around you in a completely different way. It teaches you to find beauty and impact and symbolism in places that most people wouldn’t grace with a second look. Photography teaches you to pay attention and to appreciate. It’s about seeing much more than it is about capturing what you see. […] Practicing photography in a mindful way makes the world around you more visually stimulating and your experiences richer.

Taking photos in a “mindful way” is the key here. I think the critics of mass photography are assuming all this snapping that’s going on is mindless and that strikes me as a big and brutal assumption. Sure, a lot of people’s photography is technically and aesthetically awful. Lots of people don’t have that compositional eye just as many are tone deaf. But to imply it’s mindless, that no thought has gone into it, that it isn’t enabling a different way of seeing and experiencing the world, seems odd.

I’m going to make my own assumption now, so feel free to discard it, as I may well do in the future. The rejection of mass photography come from a desire to return to a time when photography was an elitist pursuit. Derogatory terms like “snapshots” and the fetishisation of expensive equipment helps establish this. People using cheap, disposable cameras believe they are incapable of taking amazing photos because they don’t have the right equipment, despite some of the best photos in history being taken with compacts.

It’s seems to be a given by the “professional” and “artistic” photography crowd that only they are able to be mindful in their photography practice, which helpfully distinguishes they from the masses who threaten their hallowed position. For if some civilian with a cameraphone can produce images of great value, where does that leave them?

Needless to say I have very little sympathy with that straw-man I just constructed. The ubiquity of cameras is exciting, not because of the flood of images, but because it gives everyone the ability to practice photography mindfully, regardless of their background.

Before I move on, James Shakespeare’s Stop Externalising Your Life is another rant against photographic ubiquity, concentrating on the the sharing of experiences online. It’s a seductive argument but I don’t think it’s useful. A couple of examples:

I don’t think that it’s inherently wrong to want to keep the world updated about what you’re doing. But when you go through life robotically posting about everything you do, you’re not a human being.

Who actually does this? Do you know anyone who posts about everything they do all day every day? Outside a few hyperactive teenagers, who will soon grow out of it, no-one behaves remotely in this way. It’s utterly implausible.

You are not enriching your experiences by sharing them online; you’re detracting from them because all your efforts are focussed on making them look attractive to other people.

This is audacious beyond words. He’s assuming that by engaging with an experience and turning it into a sharable piece of media, the experience is irrefutable reduced in impact. There’s no room for the notion that this engagement with the subject with a tool might result in a deeper understanding of or relationship with it.

It also betrays a massive lack of self-confidence. How is presenting the moment in a way which others might enjoy a submissive, reductive act? The language of social media might revolve around “likes” but that doesn’t automatically relate to pat-on-the-head praise.

It’s a very annoying point of view.

Returning to the actual act of taking photographs…

The Constant Moment is a term that has gathered a bit of steam of late, coined by Clayton Cubitt back in May. The basic premise is one that is core to my thinking about photography as a mechanically mediated artform. Cartier-Bresson’s Decisive Moment “is not about the art, but mainly about the tools that he had access to”. A portable compact camera allowed him to be discrete while the limitation of a roll of film meant he had to decide which fraction of second to capture.

Cubitt’s argument is the technology has changed and we no longer need to worry about which moment is the decisive one. They’re all available to us.

Imagine an always-recording 360 degree HD wearable networked video camera. Google Glass is merely an ungainly first step towards this. With a constant feed of all that she might see, the photographer is freed from instant reaction to the Decisive Moment, and then only faced with the Decisive Area to be in, and perhaps the Decisive Angle with which to view it. Already we’ve arrived at the Continuous Moment, but only an early, primitive version.

There’s a lot more in the article and I recommend reading it in full, but the main question that hovers over this for me is “what about composition?”

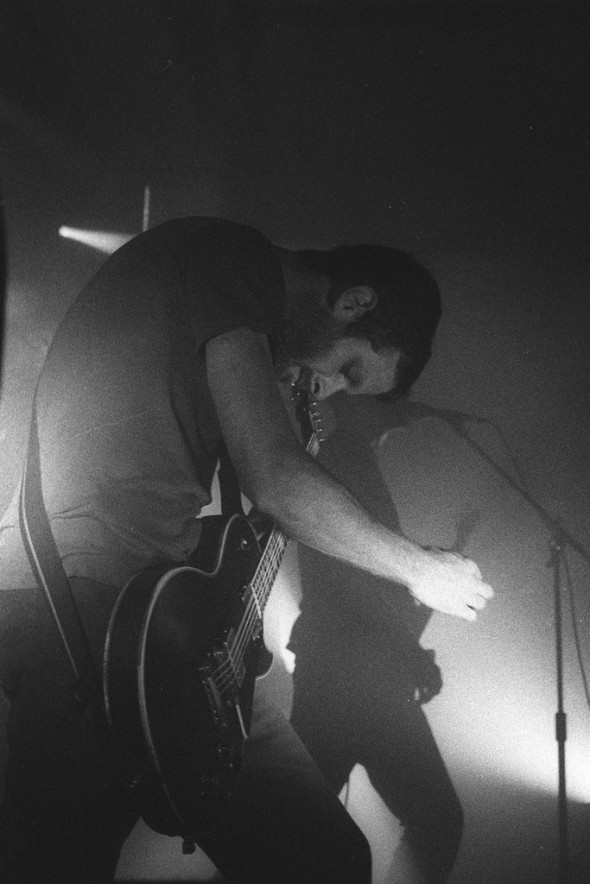

The easy version of this is the person at a gig who points their camera at the band and fills their card with 500 photos. None of them are composed - the hope is at least a few will be worth saving. The work is then done back at the computer, trawling through the gigabytes of awful blurry shots for a few passable ones. I used to shoot like this. I don’t anymore.

I learned how to shoot at gigs by going the Supersonic music festival in 2006 with a fully manual camera and four rolls of film. I budgeted I had three shots per band, so I had to find those decisive moments. I would first watch the band play, get a sense of their music and how they moved with it. If I was looking to photography a guitarist I’d understand his behaviour, see how he moved when different sections of the song kicked in. I’d get to the stage where I was comfortable in predicting their actions and then, after a few trial runs, I’d take my shot. Nine times out of ten it worked.

This harks back to Alex Furman’s “mindful photography” in that I was probably one of the most engaged members of the audience there. If I’d set up an array of 100 networked iPhone cameras across the venue and then trawled through the footage for that same shot, would that an equivalent quality of experience?

And what’s with the obsession in capturing all the moments? Surely that’s impossible, for a start, regardless of the tech, unless we’re talking about recording both the quality of light and the reflective properties of the material in that environment so it can be recreated later. That certainly comes under my broad definition of photography - capturing light information and creating images with it - but it the actual act of doing so seems irrelevant.

Maybe that’s the point - that the act of photography is no longer needed to create photographs. We merely scour the data-banks for pre-caputured light and manipulate it. This is effectively what an artist like Mishka Henner is doing with his Google Street View and Google Earth works. It is photography, no question of that, and the act of finding those scenes and screen-grabbing them does have value. To complain that an image created mediated through the Internet is of less value that one created in the “real world” would be elitist and wrong, I feel. The work that is created through trawling the Constant Moment should stand or fall on its own merits.

But I’m not really interested in the images. I’m interested in the act. I want to take people on a walk and have them engage with their surroundings using their image-making machines. Whether they produce photos of any critical worth is surprisingly secondary. It’s all about the moment.

Like I said, I’m not convinced my arguments aren’t bundled up in my own elitist prejudices about what photography “is”. I’ll keep prodding them over the next few months.

See also: Kottke musing on Constant Photography.